The Haves and Have Nots

Summary

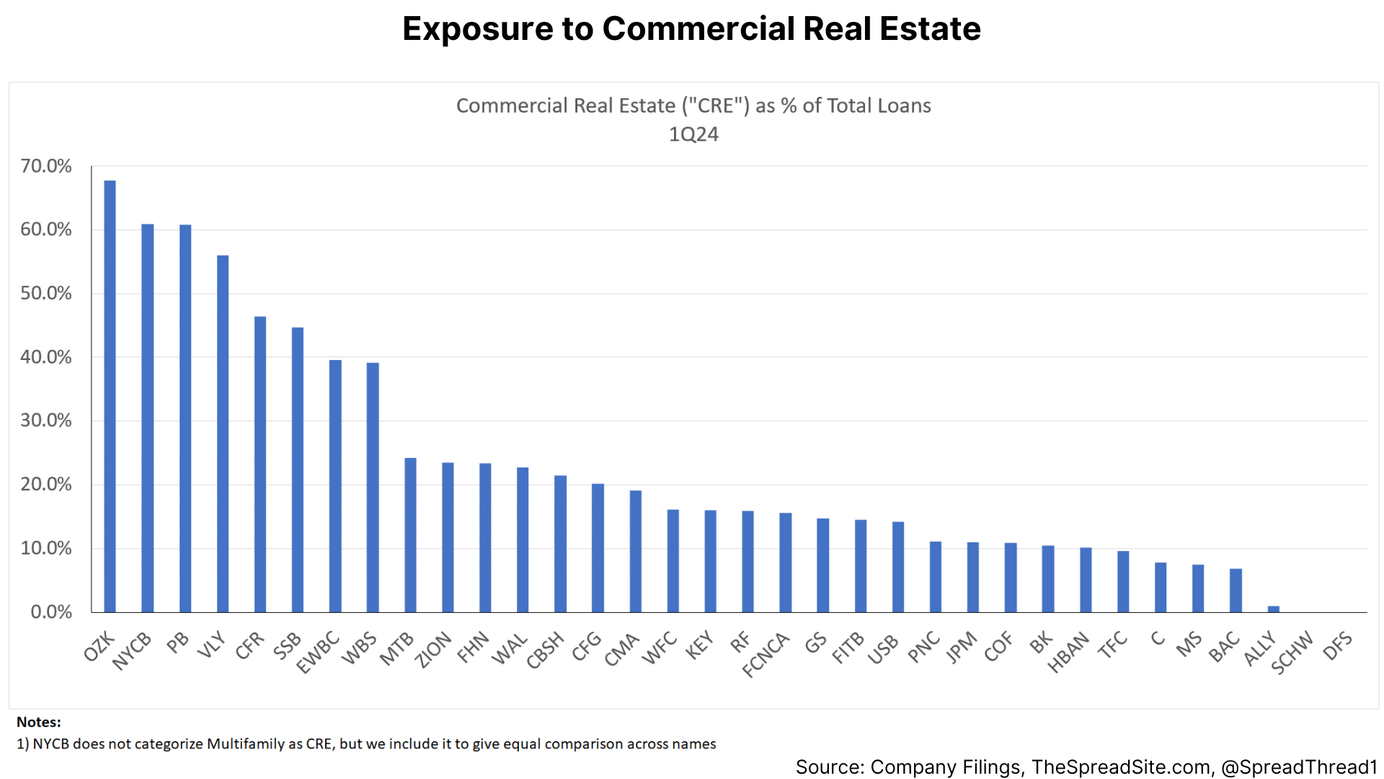

- We often hear about the health of balance sheets, yet corporate, consumer and CRE defaults are all rising, now likely beyond the point of just ‘normalization,’ despite historically low unemployment. In our view, aggregate macro data at times misses the bifurcation under the surface that will impact defaults (and the economy) going forward.

- Focusing on non-financial corporates in the Russell 3K, 87% of the cash is held by 20% of companies. Debt is not quite as lopsided with 72% of total debt sitting with 20% of companies. And 20% of companies generate 88% of the total EBITDA. The bottom 60% generate no EBITDA in aggregate.

- We think the most accurate representation of what is going on - a small number of very large companies are thriving, while a large number of small companies are not - dealing with compressing margins, higher leverage, floating-rate debt, and in some cases little access to credit. The US consumer is equally bifurcated.

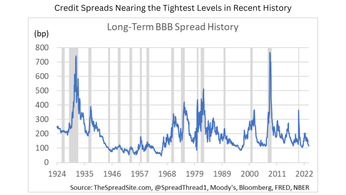

- Does it matter? In our view, problems will spread. Parts of the economy simply don’t work at the current cost of debt. As time passes, a greater number of companies, consumers and CRE owners will have to borrow at prevailing rates, either to refi existing debt or for necessary spending. Whether the stress spreads quickly or remains in the background is the key question.

Introduction

We routinely hear the argument that consumer and corporate balance sheets are healthy, and that is muting the impact of rising rates. Some even argue that rising rates are helping consumers, who are now benefitting from higher interest income on their savings. Yet at the same time, corporate, consumer and commercial real estate defaults/delinquencies are all rising, now likely beyond the point of just ‘normalization,’ despite historically low unemployment.

How can those two dynamics both be true? Putting aside the argument of whether balance sheets are in fact healthy (which we have opined on in detail previously) – aggregate statistics showing the quality (or lack thereof) of balance sheets usually miss the fact that cash, debt, leverage, interest expense, etc., is not evenly distributed throughout the economy. This is an obvious point, but an important one. In other words, some companies and consumers are in great shape, enjoying large incoming interest payments on their cash stockpiles. Other companies and consumers are struggling under the weight of high prices, high interest costs and high debt loads. This bifurcation matters, both for the default cycle, and ultimately the economy, which we will describe in more detail below.

It's Not Evenly Distributed

First, on the idea that companies in aggregate now have cash rich balance sheets, below we show the distribution of cash and debt for all the non-financial corporates in the Russell 3000 (R3K). Not surprisingly, a handful of large companies hold a significant amount of the total cash outstanding. And though the market is always bifurcated in this way, we would argue this uneven distribution is even greater now, given the size and dominance of mega-cap Tech today. We also show the distribution of debt across R3K non-financials, and while the chart looks similar to the cash distribution, we note the big debt holders (i.e., Verizon and AT&T) do not overlap perfectly with the most cash-rich balance sheets.

This next Exhibit below makes a similar point, but breaks down total cash, debt and LTM EBITDA by quintile. As the chart shows, 87% of the cash is held by 20% of companies. Debt is not quite as lopsided with 72% of total debt sitting with 20% of companies. EBITDA is actually the most extreme. 20% of companies generate 88% of the total EBITDA. The bottom 60% generate no EBITDA in aggregate.

Finally, below we show the distribution of leverage (total debt/ LTM EBITDA) for R3K non-financial corporates. Here the distribution is more even across the market, in part because leverage is a ratio. But there is still some bifurcation, with a large number of very healthy companies (levered under 2x) and a large number of highly levered and/or negative EBTIDA companies. And importantly, this data only captures publicly traded companies. We are leaving out the many high yield and leveraged loan issuers (broadly syndicated and private credit) that are not publicly traded, which would clearly skew towards the more levered buckets.

Similar to all the cash on balance sheets, many also argue that rising interest costs are manageable because most companies have fixed rate debt issued at low interest rates. As we show below, a little over 40% of corporate debt is made up of floating-rate loans, likely a higher percentage than commonly perceived. But the more important point once again: The averages skew reality. A typical company is not 60/40 bonds/loans. Large publicly-traded non-financial companies have mostly fixed rate debt still at relatively low coupons (though that is changing as time passes). While many smaller companies without access to public bond markets have capital structures containing predominately floating-rate loans. In fact, the percentage of non-fin corporate debt made up of loans has grown quite a bit over the past five years, given the rapid growth in floating-rate markets like private credit.

Adding everything up, we think the most accurate representation of corporate America is that a small number of very large companies are clearly benefitting from the current environment. They can manage cost pressures better than peers given their size and scale, they don’t need to raise debt, and they are earning high interest rates on their piles of cash. But on the other end of the spectrum, there are a very large number of small companies (especially if we include small businesses) that are losing. They are dealing with compressing margins, have higher leverage, floating-rate debt, and in some cases little access to credit. And of course, there are many companies in between.

This bifurcation is why corporate defaults are rising, despite a lot of cash on balance sheets in aggregate and termed out debt. Remember, the ‘average’ company does not typically default. Companies that began the cycle with too much leverage, and/or a very weak business (i.e., the ‘tail’) drive bankruptcies in a recession. Investors should pay more attention to ‘the tail’ in thinking about where defaults (and ultimately the economy) are likely headed.

Similar Consumer Bifurcation

We think the story is very similar looking at the US consumer. The consensus view is that consumer balance sheets are healthy. Yet delinquencies have been rising across most consumer credit categories, even before student loan repayments resumed. Once again, the explanation is straightforward. Some consumer balance sheets are extremely healthy, skewing averages. The cohort buying homes/cars with cash, sitting on the couch earning 5% in their savings accounts is doing quite well. But in all likelihood, the ‘excess savings’ that remain are mostly sitting in the accounts of these individuals with a lower marginal propensity to consume.

Additionally, the cohort that has run out of savings likely overlaps in a big way with the cohort now having to pay back student loans, as well as the individuals who have to borrow to buy a car and those priced out of the housing market. Similar to our point on corporate defaults, this bifurcation is likely why delinquencies are trending higher, even with low unemployment, and seemingly healthy aggregate consumer balance sheets.

Does It Matter for the Macro?

The key question is whether a slow/steady rise in defaults/delinquencies for the weakest borrowers really matters for the broader economy and markets. Ultimately we need to ask:

- Will the problems spread?

- At what speed?

The first point is a near certainty, in our view. Very simply, a portion of the economy doesn’t work at the current cost of debt. As time passes, a greater number of companies, consumers and CRE owners will have to borrow at prevailing rates, either to refinance existing debt or for necessary spending.

Additionally, if weak companies/consumers have been struggling while unemployment is near record lows, it is highly likely these dynamics get worse if the job market softens even modestly. And remember, all consumer don’t have to cut spending to impact the economy. If a large enough cohort is stressed, that can be enough. We are in the point of the cycle where rising corporate/consumer stress leads to cost cuts (ultimately labor) which causes more credit issues, in a negative feedback loop. Typically, this loop does not solve itself without a circuit breaker from policy makers (i.e., rate cuts).

That said, we have less conviction on the second point. If this process happens slowly and in the background, markets may ignore it for longer. The catalysts to speed things up: A break in the labor market, another unexpected credit event or some other driver of much tighter financial conditions. While we can’t pinpoint the exact timing, we do know these three catalysts are more likely to materialize in an environment where Fed policy is restrictive and defaults are rising, like today.

Disclosures

Please click here to see our standard Legal Disclosures

The Spread Site Research

Receive our latest publications directly to your inbox. Its Free!.